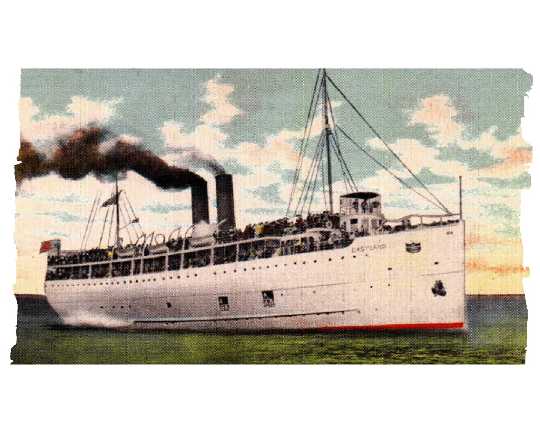

Eastland

Disaster

Wacker

Drive between Clark and

Chicago

has been known for disasters, loss of life and violence in the past. Chicago’s worst disaster to date was the capsizing of the SS Eastland on July 24,

1915. Estimates range as high as 844

people who drowned just a few feet from the loading ramp or below decks when the

heavily-overloaded pleasure boat spilled to one side.

The Eastland was in 1903 for the Michigan Steamship Company and was officially launched on May 6th. The Eastland was designed as a twin-screw ship with high-rising steel sides and a fender strake, as distinct from a steamboat with overhanging guards and a wooden superstructure. The ship was designed to carry 2,000 passengers with sleeping accommodations for 500, however, on July 2, 1915; this was upgraded to 2,500 with the addition of three boats and six rafts. The gangways were built so low that, from the outset, the ship had a small range of lateral stability. When the aft gangways were 18 inches above the waterline, a list of only some 7.5 to 10 degrees was enough to bring water onto the main deck.

She

was side-launched at 2:30 p.m. into the Black River at

Since

1911 the Hawthorne Club in south suburban

Saturday,

July 24, 1915 was the day of the annual company picnic.

Seven thousand tickets were distributed to company workers and their

families living in the

That

morning, the Eastland was moored from its starboard side to docks on the south

side of the Chicago River near the

Built

of steel and four decks high, the ship’s nickname was “Speed Queen of the

Lakes.” Its 22-mile-an-hour slice

through the water was due to its unusually narrow width of 36 feet.

Sure, there had been rumors of its instability, but there had been the

dare offered by one of the ship’s owners; a $5,000 reward for the man who

could prove that the Eastland was unsafe. No

one took the bait.

At

6:30 a.m., preparations began for loading. The

river was fairly calm. There was no

wind and the skies were partly cloudy. The

Eastland was scheduled to depart at 7:30 a.m.

At this time, 5,000 people had already arrived and were waiting to board,

so when the gangplanks were lowered, people rushed in so that they would not be

denied a chance to ride the Eastland. The

majority of those preparing to board the ships were actual employees of Western

Electric. Because the company picnic

was an important social event, a great many of the employees in attendance were

young, single adults in their late teens or early 20s.

At

6:40 a.m., passengers began boarding the ship.

At 6:41 a.m., the ship began to list to starboard (towards the dock), but

this was not unusual as it was due to a concentration of boarding passengers who

had not yet dispersed throughout the ship and were lingering on the starboard

side. But, as the list hindered the

continuation of loading slightly, the Eastland’s Chief Engineer, Joseph

Erickson, ordered the port ballast tanks to be filled to help steady the ship.

By 6:51 a.m., the ship evened out.

At

6:53 a.m., the ship began to list again, this time to port.

When the list reached 10 degrees, Erickson ordered the starboard ballast

tanks to be partially filled. The

list was straightened temporarily, but, as passengers were loading at an

approximate rate of 50 per minute, the passenger count had reached capacity by

7:10 a.m. At this time, the ship

began to again list to port. The

port ballast tanks were emptied, but the port list increased to approximately 15

degrees by 7:16 a.m. Within the next

few minutes, the ship straightened again, but the port list resumed at 7:20

a.m., at which time water began coming into the ship through openings on the

lower port side. Even so, no great

panic occurred among the passengers. In

fact, some began to make fun of the manner in which the ship was swaying and

leaning.

While

this was occurring, the gangplank was closed and most passengers on the ship

migrated to the port side where they had a view of the happenings on the river

rather than a view of the dock. By

7:23 a.m., the list had become too severe that the crew directed passengers,

many of whom were on the ship’s upper decks, to move to the starboard side.

However, by 7:27 a.m., the list had reached an angle of 25 to 30 degrees.

More water began to flow into the ship from openings in the port side,

and chairs, picnic baskets, bottles and all sorts of items began to slide across

the decks. Still there was no

general panic. The band on the Theodore Roosevelt, playing “I’m on My Way to

At

7:28 a.m., the list had reached 45 degrees.

At this point, many of the crew began to realize the seriousness of the

situation. Many more passengers were

now on the port side of the ship, as they had gone there to view a passing

Some

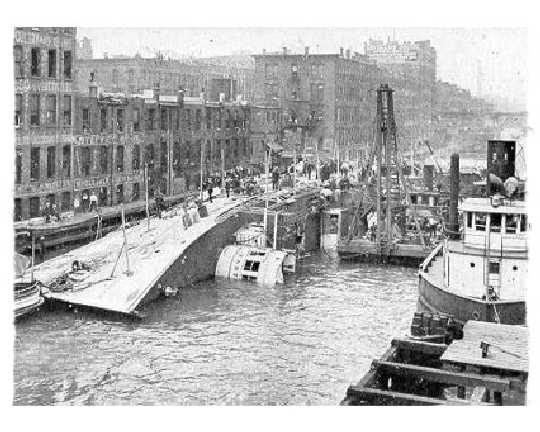

passengers who had pulled themselves to safety were fortunate to find themselves

standing on the starboard hull of the Eastland.

Others who were not so lucky were trying to stay afloat in the currents

of the river. Others were trapped

within or under the Eastland. One

eyewitness described the scene:

Some

passengers who had pulled themselves to safety were fortunate to find themselves

standing on the starboard hull of the Eastland.

Others who were not so lucky were trying to stay afloat in the currents

of the river. Others were trapped

within or under the Eastland. One

eyewitness described the scene:

“I shall never be able to forget what I saw.

People were struggling in the water, clustered so thickly that they

literally covered the surface of the river.

A few were swimming; the rest were floundering about, clinging to a life

raft that had floated free, others clutching at anything that they could reach -

at bits of wood, at each other, grabbing each other, pulling each other down,

and screaming! The screaming was the

most horrible of all.”

Other

boats in the area and people nearby began helping with rescue operations

immediately. Some onlookers dove

into the river or jumped onto the boat to help those who were struggling while

others threw wooden planks and crates into the water to help people stay afloat.

The crews of other ships were pulling people out of the water, dead and

alive. By 8 a.m., all survivors had

supposedly been pulled out of the river. Ashes

from the fireboxes of nearby tugboats were spread over the starboard hull of the

Eastland so rescue workers would not slip on the wet and slick surface as they

cut holes in the side of the hull to pull out survivors as well as dead.

The screams coming from those inside the ship were disturbing for

onlookers. By the time the holes

were cut in the hull, many who had been alive at the time the ship rolled had

since drowned. A great effort was expended to remove the dead from inside the

ship as divers had to go underwater within the hull to retrieve bodies.

A

major problem occurring immediately after the disaster was the vast amount of

bodies that needed to be laid out in order to be identified.

As the Western Electric employees were not assigned to ships, no

passenger lists existed and none were written as the ship was boarded.

By Saturday afternoon, the Second Regiment Armory on

The

total death toll was 844 people. Eight

hundred and forty-one were passengers, two were from the crew, and one was a

crew member of the Petoskey who died in the rescue effort.

Although the Titanic, which sank three years before in 1912, had a higher

total death toll of 1,523, the Titanic actually had a lower death toll of

passengers than the Eastland as crew deaths from the Titanic totaled 694.

And, the ironic part is that all these people died in just 20 feet of

water in downtown Chicago, just a few feet away from the safety of the dock and dry land.

Salvaging

the ship was not an easy task. While

raising the ship, difficulties were encountered in getting it to float as so

much water needed to be pumped out of the hull.

The ship was finally refloated on August 14th.

The

Eastland was acquired by the Illinois Naval Reserve four years later, after

several modifications which enabled the ship to serve safely as a training

vessel. The ship, re-named the USS

Wilmette, served for several years until it was decommissioned in 1945.

The ship was then sold for scrap, and by early 1947, the ship was

completely disassembled for parts and metal.

A

bronze plaque was erected on the site, Sunday, June 4, 1989 and there were

thought to be only four survivors alive from the disaster.

However, only Libby Hruby, 84 at the time, was in sufficiently good

health to attend the ceremony.

For

a number of years now the area where so many lost their lives has been the scene

of strange paranormal activity, namely sights and sounds.

Pedestrians strolling past the site, particularly in the evening, often

hear a loud commotion in the water as though a number of people are floundering

around. Screams and splashes are the

most often encountered type of sound heard by people near the area.

Of course, when they look from the overlook, they see nothing amiss and

the water perfectly calm.

Some

have seen a large wash of water suddenly overflow the river walk area of lower

It may take quite sometime for the energies to dissipate sufficiently for the paranormal activity to cease altogether. Until then, the ghosts of the Eastland will be encountered.

![]() Ghost Research Society (www.ghostresearch.org)

Ghost Research Society (www.ghostresearch.org)

© 2011 Dale Kaczmarek. All rights reserved.

Web site created by Dale Kaczmarek